Click here to download a high resolution PDF print file or scroll down to read the entire guide online.

Table Mountain is one of the most recognizable mountains in the world, along with Mount Everest, the Matterhorn, Mount Fiji and the Sugar Loaf Mountain of Rio de Janeiro. Yet Table Mountain is only just higher than 1000m – quite small in comparison with the mountain giants of the world. When one sees Table Mountain for the first time, however, all statistics fall away. Rising almost straight from the sea to a height of more than three times that of the Eiffel Tower, ending in a virtually flat-topped mesa, flanked dramatically by Devil’s Peak (1000 m) on the left and Lion’s Head (670 m) on the right, this sight is magnificent evidence of nature in all her splendour. But nature does not stop here – she sites the mountain in the middle of the richest floral kingdom in the world and then goes a step further by placing it at the end of the continent, on the tip of Africa.

Table Mountain looks particularly dramatic when it has white clouds rolling over it as often happens when the south-easterly wind blows. (This wind is known as the ‘Cape doctor’ because it disperses pollution and smog over the city.) These clouds are in fact formed by condensation when the moisture-laden air rises and makes contact with colder air. The clouds dissipate as they roll down the front of the mountain and meet warmer air. There is, however, a far less scientific story about the formation of the clouds. The legend of how Table Mountain got its tablecloth concerns a Dutchman, Van Hunks, who used to sit smoking his pipe on the saddle between Devil’s Peak and Table Mountain. One day a stranger approached him and challenged him to a smoking contest. When the stranger finally collapsed, his hat fell off to reveal the devil’s horns. In the meantime the vast quantity of smoke they had produced had blown across Table Mountain, looking like a cloth laid on its top and adding to its spectacular visual impact.

It is no wonder, then, that on seeing Table Mountain and the Cape Peninsula in 1580, Sir Francis Drake (the first person to sail around the world) wrote in his log: ‘The Cape is a most stately thing, and the fairest Cape we saw in the whole circumference of the earth.’ It is also not surprising that Table Mountain earned the prestigious title of one of UNESCO’s World Heritage sites in 2004 and was chosen as one of the new Seven Natural Wonders of the World in 2011. But there was a time where Table Mountain would have not won a single award as it looked very different from the way it looks today.

Long ago

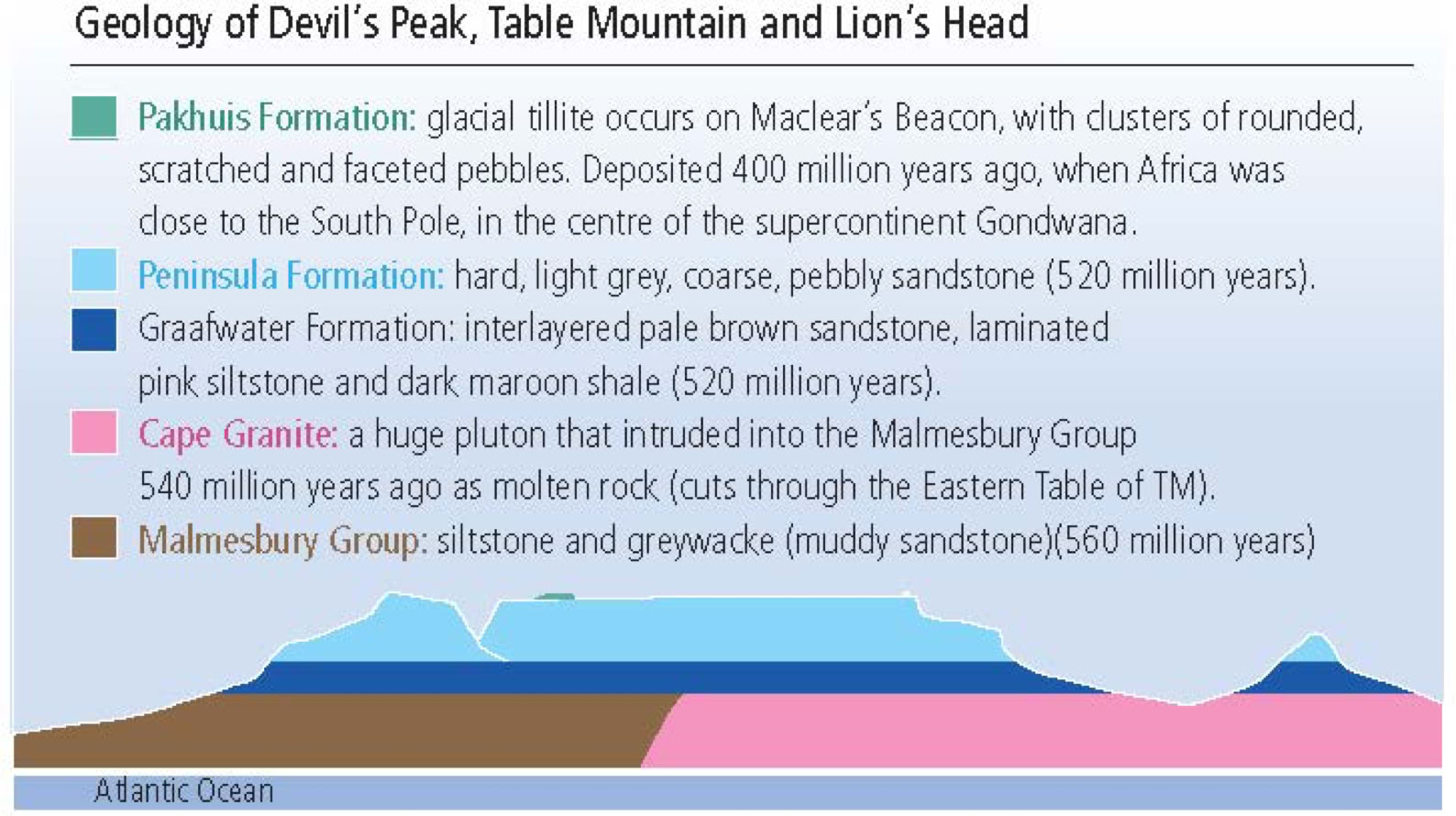

In prehistoric times, Table Mountain did not exist. It all started about 560 million years ago when the foundation of Table Mountain – known as the Malmesbury Group of siltstone – was laid down. This siltstone, which underlies most of the area you can see from the top of Table Mountain, was laid down under a now-vanished Adamastor Ocean and was subjected to compressive pressure, which folded the beds. At the same time, about 540 million years ago, an intrusion of molten granite pushed its way up, creating the foundation for most of the mountain chain of the Cape Peninsula. Where these two different rock types meet, along a line under the northern edge of Table Mountain, thermal metamorphism has taken place. Charles Darwin visited the Sea Point contact to view this wonder of nature. Exposed granite can be seen at its best on the Sea Point side of Lion’s Head.

An early cableway used in the construction of the reservoirs in the late 1800s

About 500 million years ago, riverine and estuarine sediments (to a depth of 1700 m) were laid down as far as you can see from the top of Table Mountain. The first of these sediments to be laid down were thin beds of red micaceous shale and brown quartz sandstone of the Graafwater Formation at the base of the Table Mountain Group. The second formation, 650 m of thick-bedded quartz sandstone, is known as the Peninsula Formation. On the summit of Table Mountain is the Pakhuis Formation, 35 m of tillite left behind when the Ordovician Ice Age ended, about 400 million years ago. You can see remnants of this formation around Maclear’s Beacon today. Above these three formations, but not visible today as they have been eroded away, were yet another four formations, the first being of laminated, fossiliferous claystone and the top three formations all being quartz sandstones.

The lower cableway station on Tafelberg Road

About 130 million years ago (at the time of the break-up of the supercontinent Gondwana), a great change took place – the mountain rose out of the water in successive periods of simultaneous upliftment and erosion. Erosion finally isolated Table Mountain from the rest of the Cape mountain system. A few million years after this, we find Table Mountain as we see it today and, in a few million years from now, this great mountain will probably be no more, due to the force that shaped it, erosion.

Table Mountain makes up a portion of the Cape Peninsula mountain chain. The actual table is 2 km long with an average width of 300 m. Its highest point is at Maclear’s Beacon (1084 m). This section is divided into the Western Table, Central Table and Eastern Table. To the south the mountain drops by 300 m to the Back Table. This area is made up of valleys and ridges and is home to a number of dams. Two ridges jut out from this section. The first is on the right, looking south; this is the Twelve Apostles, once named Gable Mountains by the Dutch. This ridge ends at Llandudno Corner. The other shorter ridge, on the southern suburbs side, drops down and ends at Constantia Nek.

The coming of man

The first people to live in the shadow of this bastion were Stone Age people. We know this because of evidence of Stone Age implements found within the Dell in Kirstenbosch Garden. Later the Khoi and San made the foot of the mountain their home. Sadly, there is no evidence that they scaled its lofty heights. What we do know is that they considered it important enough to name: they called it Hoerikwaggo – Mountain in the Sea.

The coming of explorers

There are stories of Chinese and Arab sailors rounding the Cape, but the first record of Table Mountain being seen by the European world involved the Portuguese. On his voyage to find a sea route to the East Bartolomeu Dias had sailed around the Cape without realising he had done so. After sailing as far as Mossel Bay, he retraced his route, and passing the Cape the second time, he more than likely saw Table Mountain.

A historical plaque found at Maclear’s Beacon

In 1503 another Portuguese navigator, Antonio de Saldanha, put ashore in Table Bay as a result of a navigational error. Thinking he had rounded the Cape, he disembarked and climbed Platteklip Gorge to the top of what he named Table of the Cape of Good Hope to ascertain whether this was the case. The view over False Bay indicated that he had not. On descending he also discovered fresh water – a godsend for any explorer spending long periods at sea. Table Bay thus came to be known as Aguada de Saldanha (the watering place of De Saldanha) until in 1601 it was renamed Tafel Baaij by the Dutch navigator Joris van Spilbergen. (When Van Spilbergen put in at what he mistakenly thought was Aguada de Saldanha, he applied the name to what is now Saldanha Bay, 100 km up the west coast.)

Variations in name also affected Devil’s Peak, Lion’s Head and Signal Hill, as the Dutch and the English had their own names for these. (See the relevant Gateway Guides for further details.) Two Englishmen made a loose attempt to claim Table Bay for King James in 1620, but nothing came of this and it was left to the Dutch to take the history of the Cape a giant step forward when Jan van Riebeeck arrived in 1652 to establish a refreshment station.

Sunset at the Upper Cableway Station on the top of Table Mountain.

The settlers and the mountain

In 1652 Jan van Riebeeck stepped ashore at Table Bay, marking the first time in South African history when the visitor became a settler. On 26 September 1652 Van Riebeeck completed a climb of Table Mountain with 10 other people, one of whom was ‘Herri,’ a Hottentot (a derogatory name given to the indigenous clans by the Dutch at that time) who made the first recorded ascent of the mountain by a non-European of African descent. On reaching the summit, they lit a large fire (not encouraged by SANParks today!) to let the small settlement below know of their achievement.

There are a number of documents giving details of these early explorations to the summit of Table Mountain. Several difficulties are referred to in all accounts: toil, heat, wind, endlessly fighting through bush and being impeded by small and large rocks. In all fairness, a walk from the seashore to the top is a long way. Today, this walk starts from Tafelberg Road which gives one a 400 m height advantage and the early explorers of the Table did not have the well-made paths to the top that we are privileged to have today.

In 1679 Nicolaus de Graaff became the first settler recorded as having slept on the summit of the mountain. He took the standard route, Platteklip Gorge, with two companions. The summit was reached at 1.30 pm, whereafter they spent a while walking around. When it was time to descend, De Graaff informed his companions of his intention to spend the night on the top. At 5 pm his companions left him for the safety of the settlement far below. De Graaff tells us that he walked around until 8 pm, when he found some ‘scrubs’ between some rocks for a bed. Having no weapons for protection, the constant thought of being devoured by ‘lions, bears, tigers and other wild beasts’ gave him a sleepless night. His fears concerning these creatures were not that far-fetched as lions, jackals and hyenas are recorded as having been among the fauna of the area at that time. In fact, the last lion was shot on Lion’s Head in 1802. The next day he arose, and instead of descending to safety, he spent the day exploring the summit. He returned to join civilisation via Platteklip Gorge only that afternoon.

For the next 50 years, there was a lull in recreational climbing of the mountain. Then Carl Peter Thunberg, a distinguished Swedish botanist, arrived on the scene. His association with Table Mountain, bearing in mind his interest in plants and the wealth of its flora (much of it as yet undiscovered or undocumented) was like a match made in heaven. He made 15 ascents of the mountain; he slept on the summit, as De Graaff did, and he was the first to mention a number of routes to the summit – prior to this, Platteklip was the only route used. In 1773, accompanied by a few companions, he made the first recorded traverse of the mountain, starting up Platteklip Gorge, then descending the ridges and valleys that make up the Back Table. He continued down to Constantia Nek, known then as Baviaans Kloof. To finish their epic excursion, they walked down to Hout Bay.

Views of the Hely-Hutchinson (left) and Woodhead reservoirs on the Back Table with Constantiaburg Mountain behind

The next person to enrich the history of Table Mountain was Lady Anne Barnard, who was the first European woman to climb it, in 1797, the year she arrived in the Cape. There was no more fitting person to claim this distinction. She was the wife of the Secretary of the Colony and the official hostess of the Governor, Lord Macartney, as his wife did not accompany him to the Cape. She had a lively mind, and through her letters, diaries, sketches and paintings, we are given a profound insight into details of life in the Cape at the time. The party carried tins cases in which to place plants they wished to collect, and a hammer for collecting geological specimens. Among the group was John Barrow, private secretary to Lord Macartney, on whose instructions he travelled widely in the Cape. He subsequently published Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa and was a key figure in the founding of the Royal Geographical Society. On reaching the top she and her companions had a ‘splendid and happy dinner’ of cold meat, Port, Madeira and Cape wine. They then sang ‘God save the King’ before descending. Three years later she accompanied her husband on his first ascent to the summit, spending the night in a tent carried up by slaves.

Maclear’s Beacon (Table Mountain Pile) was built by William Mann in 1844 and was painted black so it was visible in silhouette. It is the highest point on the Table Mountain chain but the highest man-made point on the peninsula is the radio mast on Constantiaberg.

Walking from Maclear’s Beacon (seen in the background) to the front edge of Table Mountain.

A lofty home

By this stage, the mountain had been discovered, climbed, explored and slept on – the next step was for someone to make it home. In fact, people had already made it their home 27 years prior to Lady Anne Barnard’s arrival in the Cape. Runaway slaves, about whom little is known except for reports of walkers being harassed and robbed by them, lived in caves.

The first person of European descent to make his home on the mountain (for 14 months in 1799-1800) was an American sailor by the name of Joshua Penny. The irony is that he did not have to live there for as long as he did. Press-ganged into joining the Royal Navy, he found himself aboard HMS Sceptre based at Cape Town. After numerous attempts at desertion, he finally got it right and ran for the hills.

Spectacular views on the sensational Table Mountain Edge Path on the return leg of the Maclear’s Beacon walk. This path places you close to the rim of Table Mountain, so caution and safe footing are imperative.

He made his home high up in Fountain Ravine. With few possessions but considerable resourcefulness, he survived in contentment. He obtained meat by throwing stones at his prey (buck and dassies) and knocking them off precipices; the skins became clothing as his normal attire did not last long in the rugged terrain. The meat was cut into strips, dried and then boiled and eaten with a home-made sauce. Besides eating wild honey he incorporated it into a fermented drink with pounded roots. However it was not always utopia, as he reported that he had some close encounters with ‘wolves’ which must have been hyenas. Penny kept an eye on the ships in Table Bay for a safe time to return to normal life, but there were always British ships at anchor. One day there was only one ship in the bay. Penny stealthily managed to leave his home on the mountain and secure himself a position as a crew member on this Danish ship only to learn that the Sceptre had sunk in a storm two weeks after his desertion!

There are other stories of people living on the mountain such as ‘Blinkwater Johnny’ who lived there for 25 years. During WWI a family lived hidden for over 12 years – they secreted their brass bed on the mountain and two daughters were born there. Today, only rangers are allowed to live on the mountain and you can only sleep overnight if you book the Overseers Hut on the Back Table of Table Mountain.

Other interesting firsts

The first horse ride up Table Mountain was in 1798, but James Holman’s ride in 1829 was exceptional as he was totally blind. In 1937 Sidney Jarman, at the age of 72, cycled from Constantia Nek to the top of Table Mountain. The first motor car (a Baby Austin) to reach the top was driven by A.P. Cartwright in 1928. The trip took four hours. The fastest ascent of Platteklip Gorge is 27 minutes up, with a descent in 11 minutes. Table Mountain was first illuminated in 1947 during the British royal family’s visit. Paragliders first launched off Table Mountain in the mid-1980s. Base jumpers Karl Hayden and Shaun Smith plunged off the mountain in 1998. Bungee jumpers have jumped from the cable car, and in 2009 a high-line walk over Union Ravine took place. In 2021 A.J. Calitz and C. Greyling ran up Table Mountain 14 times in 20 hours to set a new world record.

The start of the Platteklip Gorge walk is on Tafelberg Road about 1 km further along from the lower cableway station.

Table Mountain originally "Hoerikwaggo" (Mountain in the Sea) as viewed from Bloubergstrand (Blue Mountain Beach)

From this vantage point both those names, San & Afrikaans, are self explanatory.

A place for recreation

The first form of recreation was a good old ‘walk up the hill’. Then, in 1889, an accident occurred in Fountain Ravine and a rescue party was needed; this incident started the ball rolling for the establishment of the Mountain Club of South Africa (MCSA), which opened its doors in 1891. Its first task was to employ eight guides, all Cape Malays, as they knew the mountain better than anyone else.

The first climbing routes were up ravines and then on ridges, and finally on the flat walls between. There were 5 routes in 1894; 10 years later there were 50, and today there are more than 800 routes. Every generation has had its leaders who took climbing to the next level – these include Jim Searle, George Travers-Jackson, Ken Cameron, J.H. Fraser and many more. Consider the flat face under the upper cable station called Arrow Final: this was climbed solo by Travers-Jackson in 1897. Searle climbed Right Face and Left Face in 1895. Today the hard climbs on Table Mountain are equal to grades of difficulty found anywhere in the world.

The MCSA is involved in all aspects of the mountain including preservation, mountain rescue, land acquisition, and they are a voice on any issue that may affect the mountain. Today Table Mountain has become home to many recreational sports such as Rock climbing, hiking, Abseiling, Mountain biking, trail running, Caving and Paragliding.

Flora and fauna

When it comes to flora, Table Mountain has much to offer, as it is situated in the Cape Floral Kingdom, the smallest but richest of the world’s six such kingdoms, containing over 8000 flowering species, of which about 2500 can be found on the Cape Peninsula, and approximately 1400 on Table Mountain. Fynbos (fine bush) is the predominant vegetation type on Table Mountain, with many species of proteas, ericas and restios to be seen. Today only small mammals make the mountain their home: there are 50 species from the lynx, porcupine, mongoose and dassie to the Himalayan tahr which SANParks have tried to eradicate as they are not indigenous, but there are a few sneaky ones left. Birds that frequent the mountain range from the smaller prinias, sunbirds and grassbirds through to larger hawks, owls and the king of Table Mountain, the black eagle. While there are snakes on the mountain, they are rarely seen. Venomous snakes include the boomslang, Cape cobra, puff adder, berg adder and rinkhals. Other smaller reptiles and insects abound.

Table Mountain as a resource

As well as using Table Mountain for recreational purposes, people have harnessed its natural resources right from the start. The first ships to round the Cape used its water. When the settlers came, they virtually wiped out its forests as timber was used for shipbuilding, firewood and furniture. Its rivers were harnessed, dammed and diverted for human consumption. The town’s washing was done in the Platteklip stream.

It has been reforested with pines, quarried for its stone, and nearly turned into a farm when an entrepreneur tried to lease the whole summit to grow hemp.

Then there was the idea that the mountain had gold and other metals worth scarring it for. All the mines ended in failure. A gold mine on Lion’s Head in 1887 and a tin mine in 1912 on Devil’s Peak were the biggest operations. In all likelihood, the most successful operation was a fake gold rush on Platteklip Gorge, started by a ship supplier who made a fortune through selling drinks and food (the real gold rush!) to the thousands of diggers.

The early inhabitants recognised the value of the water running off Table Mountain: they named Cape Town Camissa (the place of sweet waters). The availability of water from the mountain and the springs at its base is the reason Table Bay was chosen as the site of the halfway station on route to the East even though it is not the most suitable harbour on the southern coast.

As Cape Town grew to a point at which the little streams coming off the mountain could not meet the demand for water, a number of reservoirs were built; the biggest of these is the Molteno Reservoir, built in 1881. Within a short period of time, however, the inflow was insufficient to replenish the reservoir. The solution was to lay a pipe along the length of the Twelve Apostles (hence the walk known as the Pipe Track) from Kloof Nek to the Slangolie Ravine, and then cut a 700 m tunnel through the mountain to connect with Disa Gorge at the back of Table Mountain to reach the best source of water. The Woodhead Tunnel was opened in 1891.

Again the demand for water soon exceeded supply due to Cape Town’s long, dry summers. The next undertaking was the building of a large dam on the Back Table above Disa Gorge. The Woodhead Reservoir was started in 1890 and completed in seven years. The fact that all material had to be transported up Kasteels Poort led to the first cableway being installed: it was 1600 m in length and climbed 700 m. At the top, a railway line carried material to the site by means of a steam train. (It can still be seen today in a small museum near the reservoir.) Within a year a new reservoir, the Hely-Hutchinson, situated above the Woodhead Reservoir, had to be built. A new tunnel was put in place in 1960 to replace the unstable Woodhead Tunnel.

Three new dams (the Victoria, Alexandra and De Villiers) were built to supply Wynberg municipality. Cape Town’s water supply today comes largely from other sources, with these old reservoirs used for supplementation.

Growth in tourism and an interest in the outdoors saw the number of visitors grow exponentially. The cableway recorded its first million customers in 1959 and by 1990 there had been 8.5 million. Today, the cableway has taken more then 16 million visitors to the top with a perfect safety record. Upgrades to cars and equipment took place in 1958, 1967 and 1974. The 1974 cableway allowed for 28 passengers. In 1993, Dennis Hennessy, the son of Sir Alfred, the founder of the TMACC, sold the company. It was the end of an era.

The new directors planned a complete upgrade. By 1997, with very strict environmental guidelines, and the input of the National Parks Board, Cape Town City Council, consultants, specialists and contractors, and after several months of closure, the new cableway was opened on 4 October 1997. Meanwhile a new restaurant had been built, paths upgraded, new machinery installed and viewing platforms made with better views and designed in such a way that they would blend into the surroundings so as not to be seen from below the mountain. The biggest change was the introduction of the new 65-passenger revolving-floor cable cars called ‘Rotairs’ allowing passengers a 360 º view of the city and Table Mountain. This new car takes only three minutes to get to the summit.

As well as giving joy to millions of visitors, the TMACC also assists in mountain rescue and retrieval. The company will go to great lengths to help the needy as in the case, many years ago, of a retired racehorse which found itself lost on Table Mountain and ended up collapsed at the upper cable station. The staff, without fuss or publicity, organised a special free cable car ride off the mountain for the unfortunate horse.

Walks on Table Mountain

The five walks on Table Mountain covered in this guide are found on the illustration on page 1. These include the Dassie Walk, Agama Walk, Klipspringer Walk, Platteklip Gorge and a walk to Maclear’s Beacon. All of these walks can be reached from the Upper Cable Station and are flat in nature, except Platteklip Gorge which is a stiff walk up the mountain gaining 600 m in height.

Walking up Platteklip Gorge

Platteklip Gorge is 1.5 km along Tafelberg Road from the Lower Cable Station. A large sign indicates the start of the walk. Car guards will look after your car while you are on your walk – remember to tip. For the climbers of old, this walk started 400 m lower than it does today. The name of this climb was coined by Mundy who remarked on a large flat rock (platte klip in Afrikaans) found on the route. This is the gorge that provided access to the summit for the early explorers. It was also the source of water for ships sailing around the Cape, and later of drinking water for the settlement, while providing a place where laundry was done in early Cape Town. It remains the most-walked route to the summit of Table Mountain as no technical skill is required – just a good hard slog – and there are breathtaking views.

Hiking trails on Table Mountain.

Table Mountain Aerial Cableway

By 1929 there had already been a cableway and a funicular on Table Mountain, but both were used for construction purposes and were not open to the general public. The cableway, as we already know, was used in the construction of the reservoir on the Back Table. The funicular (with a car drawn up the mountain on tracks by a stationary engine fixed on top of the mountain) was used to construct the Wynberg dams. In 1870 the dream of an easy way to the top by Dr van Oppel and Captain van der Veen was put forward, but nothing came of it. Their idea was a rack railway (in which the engine is found within the car that climbs the mountain by means of cog-wheels inserted into slots in the tracks). The proposed route would have taken a direct line up Platteklip Gorge.

The post-Anglo-Boer-War depression killed the Platteklip venture. The outbreak of WWI and the subsequent depression killed a funicular venture which had been passed by ratepayers in 1913. This funicular would have started at Kloof Nek (with a great deal of damage to the mountain) and made its way up over Kloof Corner through to Fountain Ledge

The last of the ventures put forward for an ‘easy way to the top’ was the brainchild of Norwegian engineer, Trygve Stromsoe, in 1925. He proposed a cable car situated in the same position as today’s. Stromsoe, with Sir Alfred Hennessy, a highly influential man who got the project off the ground, and two major financiers, Sir David Graaff and Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, formed the Table Mountain Aerial Railway Cable Company. The lower cable station site was bought and the upper cable station site was leased from the Cape Town Municipality for 99 years. Tafelberg Road was built, Adolf Bleichart was appointed to build the cableway and architects Walgate & Ellsworth designed the cable stations and restaurant.

Many Capetonians hated this new ‘pimple’ that changed the aesthetics of the mountain. Undeterred, Stromsoe pushed on with a dedicated team, some so dedicated that the building foreman and his wife, who were living at the upper cable station, had their baby on the summit (the first recorded birth on the summit of Table Mountain).

In 1929 the 10.5 ton cable arrived from overseas. The journey from the harbour to the lower cable station took two days, using a steam tractor, followed by the threading of the 1213m cable from a small cable, getting larger until the final cable was set in place. The cableway eventually opened on 4 October 1929 on a cold, windy day, perhaps an omen for the company, for it battled financially for the next 20 years. Major contributing factors were the Great Depression and WWII. Both the financiers and Stromsoe pulled out of the venture. Sir Alfred stayed through the hard times and fortunes changed after WWII.

About 150 m above the start of the Platteklip Gorge walk, you will see good examples of the Graafwater rock formation.

Walk up the left side of the stream for about 320 m till you meet the contour path. (Refer to the main illustration on page 1 and the corresponding photographs.) At the contour path, turn left and walk for about 100 m until you see a sign that points you on your way up Platteklip. This path zig-zags all the way up. As you gain height, the gorge gets narrower and more interesting. The final 200 m is spectacular, with huge rock walls on either side, narrowing to 3 m. This route ends in a small valley on the top of the mountain. This is the junction with the Upper Cable Station walk and Maclear’s walk. Go left to Maclear’s Beacon or right to the Upper Cable Station. If you are too tired to descend via the gorge, one-way tickets for the cable car are available from the Upper Cable Station.

Upper Cable Station to Maclear’s Beacon

Start at the Upper Cable Station. Walk any of the paths provided you are walking in an easterly direction; a 650 m walk will lead you to the little dip at the top of Platteklip Gorge. A chain handrail will assist you down the steep section into the dip. At the junction here, take the path opposite, leading slightly right. The next section is a 1.7 km walk skirting the back edge of Table Mountain, looking down on the Back Table. The path is well defined with boardwalks over soggy sections. Maclear’s Beacon will come into view. The final few metres require a scramble to the summit, the highest point on Table Mountain at 1086 m (Photo 9).

Two people of historical importance are associated with the summit, the first being the Irish-born astronomer, Sir Thomas Maclear (1794–1879), who came to the Cape in 1834 and who, between 1838 and 1847, played an important role in the re-measurement of the Meridian Arc. In 1844 he supervised the building of Maclear’s Beacon as one of the beacons used for his measurements. The other person is General Jan Smuts, who walked to this summit so often that the route he took from Kirstenbosch Garden to the summit is called Smuts’ Track. He was a commando leader in the Second Boer War, led the SA forces against the Germans in South West Africa, commanded the British forces in East Africa during WWII, helped to create the Royal Air Force, and served in Winston Churchill’s Imperial War Cabinet. He is also the only person to have signed the peace treaties ending both world wars. He helped establish the League of Nations, urged the formation of the United Nations and wrote the preamble to the charter of the UN. He was also Prime Minister of South Africa.

On leaving the summit, you can take two routes back. The first is to reverse the route you have taken, which is recommended for walkers who suffer from vertigo. The second route starts from Maclear’s Beacon: walk in a southerly direction, turn left, pass a small amphitheatre (look out for the memorial plaque to Smuts on the rock face) and head off towards the front of Table Mountain overlooking Cape Town. Your objective is three large distinctive boulders on the edge of a small plateau 700 m away. You will now find yourself on the front edge of Table Mountain. Walk left along the edge on a good path that winds its way through boulder fields, taking you sometimes very close to the edge, so take care. This path will lead back into the little dip above Platteklip Gorge. This return journey is only about 100 m longer than the standard route. Leave the little dip above Platteklip, climb the handrail section and a quick walk will bring you back to the Upper Cable Station.

Safety on the mountain and conservation

Do not undertake these walks if the weather may put you in danger (weather check: call 021 424 8181) and always carry extra clothing in case of sudden changes in the weather. Also carry water and additional energy food. Let someone know the route you are taking and your expected time of return: plan sufficient time for your walk. Preferably take a mobile phone but as few valuables as possible as muggings have occurred on the mountain: avoid suspicious-looking people and try to walk in a group, never on your own. Keep to the paths in order to prevent soil erosion and damage to plants. Do not pick or disturb flora or fauna. Do not start fires or deface rocks. Take your litter home with you. Use the toilets at the Cable Station before beginning your walk. The rule of thumb is to leave the mountain as you found it.

Turning left on the Contour Path on the walk up Platteklip Gorge.

The top of Platteklip Gorge. At this junction (looking up), the upper cableway station is to your right.

For more information

Cable Car:

Ticket office at the lower Cable Station or book online

• Adults: R395 return / R220 one way

Under 18: R195 return / R120 one way

Booking: https://tablemountain.net/plan-your-visit/buy-tickets

• Concessions for children, SA pensioners, SA students, families

and Wild Card holders. It is free on your birthday!

• Times vary according to the seasons and weather conditions.

Normal summer opening hours 08h00, winter 08h30

(Closed for maintenance for two weeks during winter)

In peak season, you can catch the car up as late as 21h00

• Warning siren: a siren will sound if the weather deteriorates. Please

make your way immediately to the cable station, as this signals the

final cable car down.

• For information regarding the cable car, call 021 424 0015

or go to www.tablemountain.net.

• For a weather check call 021 424 8181.

Thanks to Shelley Brown for editorial input.

Thanks to Dr John Rogers for assistance with the geological section.

Emergency Numbers:

Police: 10111 • Table Mountain National Park Safety: 0861 106 • Mountain Rescue: 021 937 0300 / 021 508 4527

© Richard Smith

Citations available on request.

Richard Smith. 083 260 2985. richard@gatewayguides.co.za. www.gatewayguides.co.za www.historicaltimelines.co.za

© Richard Smith • Gateway Guides • 2023.

Distribution: GoSeeDo